EU Dienstrecht

Service

- Rechtsberatung, Strategie und Prozessvertretung rund um die Arbeitsverhältnisse bei den Organen und anderen Einrichtungen und Agenturen der Europäischen Union – EU Beamtenstatut (Personalstatut) / BSB

- Expertenwissen basierend auf eigener Tätigkeit in verschiedenen EU Institutionen, in der Prozessführung vor den EU-Gerichten sowie in der politischen Interessenvertretung

- Begleitung im Beschwerdeverfahren des Art. 90(2) Statut

- Gutachten

- Vertretung gegenüber den EU Einrichtungen, vor dem Gericht der EU und vor dem Gerichtshof der EU

- Beratung und Durchsetzung Ihrer Rechte bei Berufskrankheit und Arbeitsunfall, Versicherung, sowie bei Dienstunfähigkeit / Invalidität (Ärzteausschuss / Invaliditätsausschuss)

- Institutionelle Compliance und Beratung zu legislativer Gestaltung

Ausgewählte Themen und Rechtsprechung EU Beamtenrecht

What is EU Civil Service Law ?

EU Civil Service law features aspects of individual and of collective labour law which have shaped a sui generis system of employment. It is based on the Staff Regulations (SR) and the Conditions of Employment of Other Servants (CEOS) that apply to the staff of the EU main institutions, but also to equivalent European services defined as ‘institutions’ such as the Economic and Social Committee, the Committee of the Regions, the EU Ombudsman and the Data Protection Supervisor, and to the agencies and other bodies. They largely apply to the staff of the European External Action Service (EEAS). The regime of EU Civil Service law (including the jurisdiction of the courts of the CJEU under Art. 270 TFEU) is also of importance for the staff of bodies enjoying more independence within the family of European institutions, such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Central Bank (ECB).

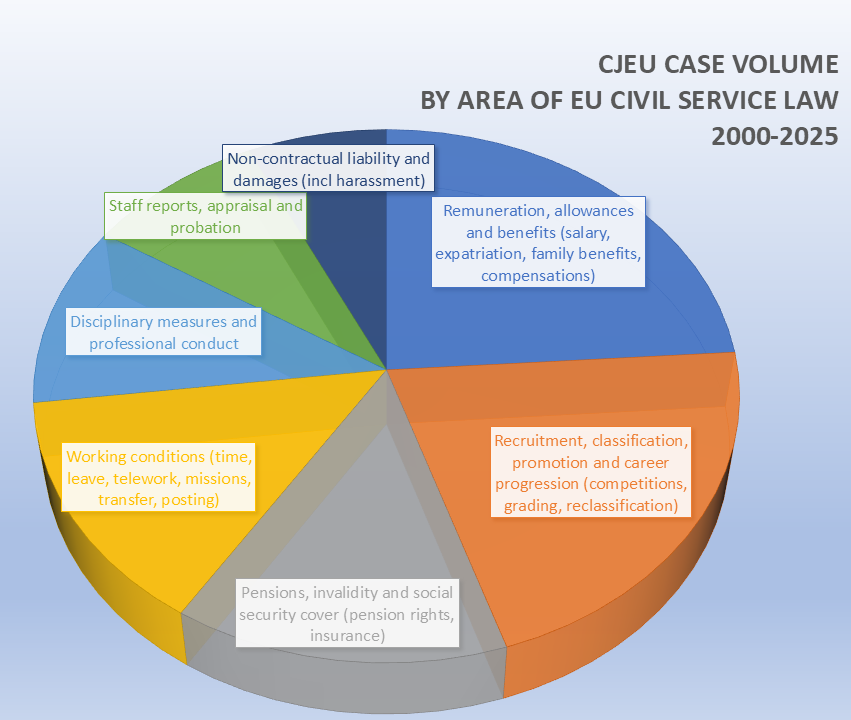

EU Civil Service law has been shaped by a large and detailed jurisprudence of the EU Courts, being the area of Union law that represents the second-largest number of cases brought before the courts of the EU (only intellectual property law produces a higher number of cases). Since 1952, a total of over 5,000 cases relating to civil service law and the Staff Regulations have been decided and settled out of a total of over 40,000 cases.

This case law has not only developed employment law in the narrow sense, but over time it has significantly spurred advances in EU administrative law, institutional law, procedural law and individual legal positions such as the EU’s stance on fundamental rights, long before a fundamental rights charter was drafted. For that reason, EU civil service law also functions – in the field of research on EU integration – as a test bed for the horizontal application of (for instance) EU procedural administrative law.

Interpretation of EU Staff Regulations

An interpretation other than by wording presupposes that the legislative intent is not clear without doubt from the legal text itself. Apart from an interpretation according to the letter, sometimes also the historical, systematic and teleological method of civil service law as an autonomous legal matter of Union law in accordance with the Treaties and general principles of Union law, is being applied by the EU Courts. A general principle of interpretation is that a measure must be interpreted, as far as possible, in such a way as not to affect its validity and in conformity with primary law as a whole and, in particular, with the provisions of the EU Fundamental Rights Charter. Another frequently applied principle is the need for a narrow interpretation of provisions giving rise to a claim, as well as the strict (i.e. narrow) interpretation of exceptions. Recourse to national law only occurs if there is an express reference to such law.

How can EU Directives have an influence on EU Civil Service Law ?

Directives are addressed to the Member States, Art. 288 TFEU. Hence – and in line with the autonomy of EU civil service law – the provisions of directives are not directly applicable to it, either when legislating civil service law under Art. 336 TFEU or when implementing the SR or CEOS.

On the other hand, there are good reasons why the institutions of the EU should not fall short of the minimum standards that the Member States set for themselves in the legislative instruments that the directives represent. In addition, directives typically contain reasonings which may point to labour law principles and the underlying concepts that motivated the legislation. Regarding how far such considerations can and should influence EU civil service law, a consistent line has not yet emerged and would have to be drawn very carefully, taking into account the special legal character and particular circumstances of the application of EU civil service law.

Altogether, there are four areas in which directives might have an impact on civil service law:

(1) in cases of an explicit reference in civil service law to the provision of a directive,

(2) in order to fill a gap in the SR,

(3) where a directive expresses a general principle of law, and

(4) as a rule of interpretation in line with the duty to cooperate in good faith.

In more detail:

(1) Explicit reference

A provision may expressly refer to an article of a directive or to a directive as a whole. Art. 1e(2) SR contains a dynamic reference to directives, which the ECJ interprets so widely that all directives relating to health protection (including the organization of working time) are included. There is reason to criticize this as going too far, partly because the SR already contain provisions on the organization of working time, and partly because a softening of the conclusive normative character of the SR would lead to legal uncertainty. In another case too the ECJ applies the reference under Art. 1e(2) SR extensively to the provision of a directive which is thereby extended into a specification of the fundamental right to paid annual leave based on Art. 31(2) FRC. This also raises doubts because, given the existing (SR) rules on annual leave, there is no scope for applying the directive provision by reference, which would otherwise lead to a low (minimum) standard in the protection of fundamental rights.

(2) Filling a gap in the SR

In its judgment on the case, the CST considered that a recourse to directives and international conventions was possible where, in its opinion, civil service law was incomplete, such as in regard to the scope of the obligation to motivate a decision that terminated the employment of a temporary agent. The provision in the directive would make it possible to complement the incomplete regulation under the SR. In the appeal, the GC no longer applied this reference.

(3) General principles of law contained in directives

Provisions contained in a directive may bind an EU institution indirectly if they express a general principle of Union law which is thus applicable to the institution. A general principle of law (not ‘only’ a principle) could, for example, be derived from the considerations contained in the preamble (recitals) of a directive. In such a case it is not the directive itself that becomes the basis, but the general principle derived from it. In Carreras Sequeros, a case in which the extent of annual leave entitlement under Art. 31(2) FRC had to be determined, the GC derived a principle of non-regression concerning standards of social protection from the text of the preamble of Directive 2003/88, and asserted the existence of a desired continuous improvement of working conditions over time. On appeal, the ECJ set the judgment aside. The ideas and reasoning on which a legislative act (directive) relies may contain or be built on a general principle of law that will transpire in the recitals of a directive.

In other instances where case-law refers to directives, it is not even expressly a “general principle” that is invoked, but rather the concept of a certain level of protection afforded to persons under directives within the Member States, which according to the courts the EU institutions in their respective areas of competence shall not fall short of. For these cases, it is submitted that this is the principle that the courts actually refer to: maintaining the level of legal protection within the institutions, as it is established under the directives for the jurisdiction of the Member States. For example, according to Art. 7 of Directive 2002/14 the Member States shall ensure that employees‘ representatives, when carrying out their functions, enjoy adequate protection and guarantees to enable them to perform properly the duties which have been assigned to them. The courts refer to this provision to argue that the dismissal of an employees’ representative on the ground of his or her status or the functions which he or she performs in his or her capacity as a representative is incompatible with the protection required by Art. 7 of that Directive, and apply this to EU civil service.

It should be noted that if general principles determined from directives ultimately lead to an interpretation of fundamental rights under the Charter, there is a risk that secondary law may be used as a standard for fundamental rights. This would be contrary to the hierarchy of norms that demands the opposite: that fundamental rights and other primary law provisions should be used to interpret the content of secondary law. However, the directive itself remains an instrument of secondary law and for that reason cannot alter, let alone overrule, either a provision under the SR or a provision contained in the FRC. It cannot overrule the SR due to the specialised legal nature of the SR, and it cannot overrule the FRC because of the hierarchical structure: the charter is on the level of primary law (Art. 6(1) TEU), and is not subject to a modifying interpretation derived from secondary law.

(4) Duty to cooperate in good faith

In its judgment on Aayhan, the CST had to decide whether a directive may be relied on as regards relations between institutions and their staff. It found that an obligation to interpret the SR in the light of directives can be derived from the principle of sincere cooperation (which at the time was termed “duty to cooperate in good faith”). The Member States have a duty to act in good faith, as do the institutions in relation to the Member States and the institutions amongst themselves. The CST concluded that the directive does not in itself comprise the basis for a plea of illegality against a provision of the SR, but it may be relied on for interpreting the rules of the SR. For instance, the directive’s provisions can make explicit the EU legislature’s intention to make stable employment a prime objective in terms of the European Union’s labour relations.

Consequently, the brief overview of the four areas mentioned above confirms that care should be exercised when resorting to directives (or principles derived from directives) to develop civil service law. In practice, taking into account the comprehensive and autonomous character of the specialised labour law regime as set out in the SR and CEOS, there hardly seems to be any room left for gap-filling or an interpretation in conformity with directives that could not also be filled from within the SR or by recourse to fundamental rights. Such an approach would further curb judicial “creativity” when deducing general principles from secondary legislation, and would therefore increase legal certainty. Conversely, fundamental rights and general principles of law do have an impact on the interpretation of civil service law.

“Invalidity” of a member of staff must be determined solely in relation to the own institution

Invalidity, occupational diseases and accidents are serious threats for the professional and private lives of staff.

Art. 78 SR (invalidity allowance) is related to the incapacity to work, while

Art. 73 SR (insurance coverage) aims at the physical and/or psychological harm for the integrity of the person.

Their scope and pre-conditions are therefore not the same. Certain definitions are however identical.

In order to claim the related entitlements, the timely and accurate action is needed, once the disease is known and the staff member has all elements available to claim his/her rights. An accident must be reported within 10 working days, which may be extended in instances of force majeure and “for any other lawful reason”.

Case law has clarified the definition of the term invalidity: invalidity in the context of the entitlement of staff to an invalidity allowance can only be interpreted as an incapacity to fulfil the duties within the own institution. If found invalid there, the staff member cannot be referred to the general labour market with the argument that he/she would be “not invalid” outside the institution.

A consequence of this is that an invalidity allowance has to be granted independent of the capacity of the staff member to perform work on the general labour market. The EU institutions and their Invalidity Committees cannot avoid the recognition of an invalidity by asserting that the staff member is still fit to work “somewhere else”.

What is an Occupational Disease ?

What is an occupational disease

The term occupational disease is not defined in the SR. The definition contained in Art. 3(1) of the Common Insurance Rules states that the diseases mentioned in the “European Schedule of Occupational Diseases” shall be considered occupational diseases to the extent that the insured parties have been exposed to the risk of contracting them in the performance of their duties.

However, this list is not definitive, as becomes clear from Art. 3(2): “Any disease or aggravation of a pre-existing disease not included in the schedule (…) shall also be considered an occupational disease if it is sufficiently established that such disease or aggravation arose in the course of or in connection with the performance by the insured parties of their duties with the Communities.”

In other words, there shall be an increased protection for those persons whose work makes them more liable to the development of certain diseases by limiting the extent of the requirement to prove that they were occupational in origin. Thus, where the disease which the official contracted is included in the European List of Occupational Diseases, he (or in case of his death, his heirs) need not show that the work was in fact the cause of the disease, but that it

plausible that the official contracted it while performing his work, that is to say, that there is a possibility that the disease had its origin in his work.

The level of evidence is reduced to plausibility where the disease (or its aggravation) is contained in the list, otherwise (i.e. if is not contained in the list), the level of evidence still does not meet strict standards demonstrating causality, but it has to be sufficiently established that the disease arose “in the course of or in connection with the performance” of the duties. This onus remains, and it will not be sufficient to show only a “potential causal link” between the performance of duties and the illness if at the same time it is highly probable, on the basis of scientific knowledge, “that the illness results from a cause that has nothing to do with the performance of those duties”

That decision regarding the possibility of a link is therefore dependent on a scientific appraisal.

For example, also psychological harassment

can lead to the development of a disease that is to be recognised as being of occupational origin, with the consequence of an entitlement to the social benefits under Art. 73 and Art. 78 SR.

What is Psychological Harassment ?

- any improper conduct that takes place over a period, is repetitive or systematic and involves physical behaviour, spoken or written language, gestures or other acts that are intentional and that may undermine the personality, dignity or physical or psychological integrity of any person”. Psychological harassment must be understood as a process that occurs over time and presupposes the existence of repetitive or continual behaviour which is ‘intentional’, as opposed to ‘accidental’.

- in order to fall under that definition, such physical behaviour, spoken or written language, gestures or other acts must have the effect of undermining the personality, dignity or physical or psychological integrity of a person. A conduct is ‘improper‘ if an impartial and reasonable observer, of normal sensitivity and in the same situation, would consider the behaviour or act in question to be excessive and open to criticism.

Recruitment: the limits of Secrecy of the selection panel’s considerations

In Case NZ (T-668/20, NZ v Commission), the Court clarifies on the limits of confidentiality of the work of the selection panel (board) in recruitment processes. The deliberations of the panel are protected by confidentiality in order to ensure its independence, see Article 6 Annex III SR. However, the duty to state reasons persists, serving to protect the candidates’ right of effective judicial review and allowing the court to assume its control function.

Facts

The applicant participated in an internal competition for administrators at grade AD 10. Although NZ scored highly and was invited to the oral test, she was not included on the reserve list, since her score (15.5/20) was below the required threshold (16/20). NZ challenged the decision, questioning how her qualitative evaluations („very strong“ on all three assessed components) translated into a lower aggregate score and not being selected.

Decision of the Court

The Court annulled the decision not to place NZ on the reserve list, because the panel had violated the duty to state reasons: it failed to disclose the raw intermediate scores and the weighting method. Communication of the overall oral test score is standard practice and generally considered sufficient, but the facts here involved qualitative assessments and contained an unexplained conversion mechanism. The Court found some ambiguity in how “very strong” ratings on all components can lead to a less favorable overall score. The panel had established internal weighting and conversion tables for qualitative assessments, but did not disclose the exact intermediate raw scores nor the weighting method to NZ.

It can be retained that neither the raw scores assigned for each component nor the weighting coefficients are covered by the confidentiality of the panel’s deliberations and must, upon request, be communicated to the candidate.

The Request for Assistance, Article 24 SR

The Art. 90(2) SR Complaint and the Correspondence Rule

Art. 90 SR contains procedures for a pre-litigation phase intended both to encourage an amicable resolution of a dispute and to delimit its subject matter. Preliminary procedures provide an opportunity – on the initiative of the official – for the administration to rectify a situation where the law permits or even obliges a correction to be made.

The rule of correspondence

(also principle of consistency or principle of the identity of the subject matter of the dispute is an important specialty in EU civil service law. It requires ‘correspondence’ or identity between the subject matter of the complaint and that of the action.

What does this practically mean?

In an later court action, only those pleas will be admissible that are closely related to the complaint. The way the complaint is drafted therefore is of high importance for the success of the subsequent legal action at court. Pleas appearing only at action stage might not be heard at the court.

What is going to be admissible in the action ?

The court will accept a substantiation and the amplification of a plea already brought forward in the complaint, as well as other grounds based on legal or factual circumstances that only became known in the course of the proceedings. The effect of the correspondence rule is that the parties (especially the complainant) limit the scope of court proceedings to that of the pre-contentious dispute at the complaint stage. New legal pleas and new lines of argumentation relating to facts that have already been introduced are barred if they had not been raised in the complaint.

The correspondence rule is violated if the court application changes the subject matter or the ground of the complaint (i.e. contesting the substantive or procedural legality of the act). The action does not have to be directed against the same decision as was the complaint, but against the same content.

N.B.: A plea of illegality (Art. 277 TFEU) can be raised for the first time at the court, and does not fall under the correspondence rule.

Legal advice for drafting a complaint and Rule of Correspondence

As opposed to the filing of an application at the court, a complaint in pre-contentious procedure does not have to be filed by an attorney. Further, the costs of the complaint procedure (i.e. legal advice at that stage) are regularly irrecoverable. Hence, frequently, a staff member is not yet being advised by an attorney during the complaint phase. Under the correspondence rule, a lack of instruction leads to a limitation of the scope of arguments in litigation and thus reduces the staff member’s chances of successful outcome.

Conversely, the correspondence rule makes it advisable (despite the irrecoverable cost) to consult a lawyer, because of the preclusion of arguments that were not introduced in the complaint stage. In addition, the professional legal assessment of a matter by a lawyer in the early phase before or during the complaint procedure can help to reduce the case load of the courts.

The A to Z of EU Staff Regulations and CEOS

- Access to Justice

- Accident

- Acts Adversely Affecting an Official

- Administrative Statuses

- Allowances, Grants and Reimbursement of Expenses

- Annual Rate of Acquisition

- Appeal

- Appointing Authority

- Appointment

- Appraisal

- Ban on Obstruction

- Barcelona Incentive

- Career Paths

- Change of Function Group

- Changes and Withdrawals of Decisions

- Collective Bargaining

- Competitions

- Complaint

- Complaint to the Ombudsman

- Compensation for Damages

- Confidentiality

- Consequences of Activity in the Staff Committee

- Conflict of Interest

- Contract staff

- Correspondence Rule

- Damages

- Dismissal

- Disciplinary Proceedings

- Disputes of a Financial Character

- Duty of Care

- Elections and other Engagement

- Equal treatment

- Expatriation Allowance

- Family Allowances

- Financial Liability of the Official

- Flexible Working Time Arrangements

- Form and Language of Application

- Freedom of Association

- Function Groups

- Fundamental Rights

- General Implementing Provisions

- General Principles of EU Civil Service Law

- Good Administrative Behaviour

- Grading

- Harassment, psychological / sexual

- Health and Safety

- Impartiality

- Incapacity to work

- Independence

- Insurance and Pension

- Invalidity

- Invalidity Committee

- Joint Committee

- Leave

- Loyalty

- Medical Committee

- Medical File

- Mobility

- Mutual Rights and Obligations

- Non-active Status

- Non-discrimination

- Occupational Disease

- Officials

- Outside Activity

- Personal File

- Principles of Interpretation

- Probationary Period

- Proportionality

- Promotion

- Recovery of Overpayments

- Request for Assistance

- Retirement Pension

- Remuneration

- Retroactive Decisions

- Review

- Review of Decisions on Invalidity

- Reviewable Act

- Right to Bring an Action

- Right to Strike

- Rights of the Defence

- Role and Functions of the Staff Committee

- Rules Adopted by Agreement

- Salary

- Secondment

- Selection Procedures

- Sickness Insurance

- Social Dialogue

- Special Allowances

- Staff Committee

- Statement of Reasons

- Survivor’s Pension

- Temporary Agent

- The Framework of Administrative Decision Making

- Time dedicated to Staff Representation

- Time Limit for Bringing an Action

- Training and Career Development

- Transfer

- Transparency

- Urgent Procedures and Interim Relief

- Whistleblower Protection

- Working Conditions

The 7 most frequent topics of staff matters in jurisprudence

- Remuneration, allowances and benefits (salary, expatriation, family benefits)

- Recruitment, classification, promotion and career progression (competitions, grading, reclassification)

- Pensions, invalidity and social security (pension rights, transfer of pension rights, invalidity, insurance)

- Working conditions and place of employment (working time, leave, telework, missions, transfer, posting, working environment)

- Disciplinary measures, professional conduct (disciplinary proceedings, sanctions, suspension)

- Staff reports, appraisal and probation (annual reports, probation reports, performance evaluation)

- Non‑contractual liability and damages (psychological harassment, non‑material damage)